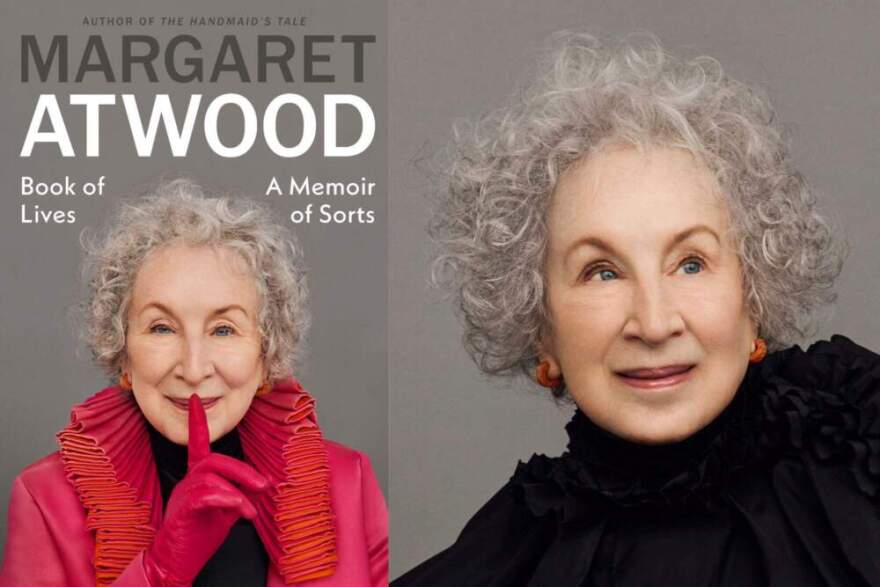

Margaret Atwood’s new memoir, “Book of Lives: A Memoir of Sorts”, is so full of life that “The Handmaid’s Tale” doesn’t appear until three-quarters of the way through.

The 1985 dystopian novel became a blockbuster TV show. The sequel, based on her 2019 Booker Prize winning novel “The Testaments” is coming in April.

But also in her sprawling memoir is her childhood in Canada, with her entomologist dad and outdoorswoman mom, a family comfortable both in academia and gutting and filleting fish, living off the grid in the wild forests of northern Canada.

There are also the mean girls in fourth grade who’d show up in her novel “Cat’s Eye.” There’s her time at Radcliffe in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Every fictional building in “The Handmaid’s Tale” exists for real in Cambridge’s Harvard Square, where I sat down with Atwood, 86, at First Parish Church, before packed pews, at a Harvard Bookstore event.

In one moment, an audience member asked which of her 50 books of fiction, poetry and commentary she’d want to save for posterity.

“That is a question for readers,” Atwood replied. “Because once you have written the book, you no longer have any control over it. And anyway, I’ll be dead,” she said laughing. “I don’t know why I’m so cheerful about this.”

11 questions with Margaret Atwood

Tell us about the fourth-grade girls. How did you carry them with you?

“They were mean, and great material. And when I wrote ‘Cat’s Eye’ some feminists said that I shouldn’t say things like that about women because they were supposed to be perfect. I’ve got news for them. Women being human beings doesn’t mean that women are perfect. It means that women are human.

Are these the girls who bullied you?

“That’s the term we’d use now, but this is much more Machiavellian. So it wasn’t, ‘You’re a terrible person, we’re going to knock you down.’ It’s, ‘We can help you. We’re your friends? But there’s some things about you that need to be improved. And we’re doing this for your own good. And I’m willing to help you in that way, too. But you have to do what I say, otherwise you won’t make any improvements, will you?’”

Margaret Atwood (left) talks with host Robin Young (right) at First Parish Church in Cambridge, Mass. (Robin Young/Here & Now)

Tell us more about the 1988 book ‘Cat’s Eye.’ In it, a woman is haunted by memories of childhood torture. You heard from a lot of people who knew that torture.

“I did. I heard from parents who said, ‘This is happening to our child, what do we do?’ I heard from men who said, ‘I never did understand what was going on in fourth grade among the girls, but now I do.’ And I heard from girls who had grown up, most of them had been in the position of Elaine, the narrator, but some of them confessed that they had been the torturer.”

Did you ever talk to your torturers after they grew up?

“Yeah. One of them became a very good friend of mine and was my partner in my puppetry business. Then I started torturing her when we were in high school.” [laughter]

Talk about the men in your life. Many wanted you to be Wendy their Peter, as in Peter Pan.

“So, I think they really wanted me to sew on their buttons because I was very good at sewing on buttons. In the novel, she does sew their buttons on. But then she grows up.”

As did you. You had a suite of poems called Power Politics that you published. One man loved when you were writing it, but when you published it, he said it was mean. You write: ‘Of course, if he hadn’t gone around telling everyone that it was about him, he wouldn’t have cast himself as my own personal hit-and-run victim. I lured him to my isles, ground my high-heeled shoe into his face or other parts and left him alone and palely loitering where no birds sing.’

“Wow, you’re searching for all the naughty, bad things I did. You were probably nice to everybody. And now you’re focused on my bad behavior.”

I am! Let’s talk about ‘The Handmaid’s Tale.’ At one point, you’re giving a keynote conference to help Amnesty International. In Argentina the military junta was in power. One of their hallmarks: Pregnant women would be kept alive until their babies were born, and then these moms would be tossed from planes into the ocean and the babies given to a general.

“Yeah. Years later, some of these people discovered their parents or who they thought were their parents had killed their parents. Imagine what that would do for you.

“As I’ve often said, I put nothing into this book that had not happened somewhere, sometime.

“For instance, Harvard and the Puritan government of 17th century New England. So, some of the fairytales that people are told is that the Puritan fathers came over and they can have freedom of religion. They came over so they can have freedom of religion for themselves.

“They did hang Quakers. Quakers used to be much more obstreperous than they are now. They used to streak congregations, without any clothes on with them, pans of burning coals on their heads.

“Anyway, the Puritan theology of New England was very interesting to me, partly because those are my folks. A lot of them came from here, went to Nova Scotia.

“That was one of the origin stories. Another one was that I grew up reading sci-fi and I had always wanted to write one. And yet another part of the origin story is that because I was born in 1939, two months after Canada entered World War II, I was very interested in how it came to this.

“How was it that dictators had been able to take over in Germany and Russia? Somebody said, ‘How does Margaret Atwood come up with all this weird s**t.’ And then my reply was, ‘It is not I who comes up with this weird s**t. It is the human race.’”

The Christian right was making a comeback?

“In 1984, which was when I was writing that book. The seventies was a very active second wave feminism. And a lot of things got changed in that decade, including married women’s rights to have their own credit cards. There was a reason [women couldn’t have credit cards], and the reason was that a man was responsible for his wife’s debts, so he couldn’t just let them loose with a credit card.

“And that was when the evangelical religious right decided to become a political force. So, I was watching that, and I was cutting bits out of the newspaper. There was no internet, and it’s a lot easier now to find that stuff.

“But even a cult that was using the term Handmaid, although it’s right there in the King James Bible and people are often surprised that I know that so well. But I’m Canadian. We did not have the separation of church and state. We had the stuff in school, not to mention Sunday school, where I did win a prize for an essay on Temperance. Why you shouldn’t drink. Would you like to know why?”

Yes.

“You shouldn’t drink because if you drink, the corpuscles in your nose will get bigger. And if you’re outside, you will be exposed to more cold and you’re much more likely to freeze to death with a very unsightly nose. I illustrated it.”

So, you hear the Christian Right is coming, and one of the tenets is going to be getting women back into the home, and you thought, ‘How are they going to do that now that they have jobs and money?’ And you say?

“Take away their credit cards. And the jobs and the money.

“And if you read this thing called Project 25, that’s one of the plans.”

Do you think about that all the time? How present is ‘The Handmaid’s Tale’ for you?

“I’m Canadian. So, we have a more existential threat at the moment. You might invade us. And I’m here to say good luck with that.”

This interview was edited for clarity.

Book excerpt: ‘Book of Lives: A Memoir of Sorts’

By Margaret Atwood

Excerpted from “Book of Lives: A Memoir of Sorts” by Margaret Atwood, published by Doubleday, Penguin Random House, an imprint of PenguinPublishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright ©2025 by O. W. Toad Limited

This article was originally published on WBUR.org.

Copyright 2026 WBUR